AKIN OLADIMEJI: Thanks for coming. This is my first in conversation, so I'm hoping it goes well. So I met the Prof in 2022 at SOAS (School of Oriental and African Studies) [...] because Jelili Atiku, who I've been doing lots of work on and got stuff published on, was involved in a show there, and you were also involved in a show there as well. They had the two of you in a panel, and I got to chat to you and learn more about your practice. Jelili said lots of positive things about you, so it was a nice coincidence when I heard that you were having a show here. So my first question is really your genesis as a painter…what made you become a painter? Because having grown up in Nigeria, I know that it's quite materialistic: certain professions are seen as highly respectable compared to others; you tell your parents that you want to be a painter, they're like, "What's wrong with you? Why can't you go become a doctor or something," you know? So, what made you decide to become a painter?

JERRY BUHARI: Yes, the narrative is a very constant one. It's almost boring, but it's true that I have a similar story. I think my interest in art started with my two elder brothers, one who was in the army and is late now, and his younger brother that I was close to – Jim. I watched them draw on the ground. You would not believe it – in my hamlet there was no paper. [...] I grew up seeing my brothers draw on ground, and that's quite humbling when I reflect that, despite the fact that they started learning from drawing on the floor, they got to school and they got to become successful in their own right. So that could be said to be my first encounter with art, or anything like art. But the next one is most interesting: my primary school – we had a good craft class. We don't call it art. It's called craft. What you are asked to do is to make handkerchiefs and to make craft work with fabric. So you did a design on a white fabric, and you took coloured threads and traced them. We had a craft teacher who was quite romantic and mysterious – as tiny as we were, he would say, “Do a handkerchief for your girlfriend.” We did that kind of stuff. I think the journey in the direction of art for me started after my secondary school. We were to go to the counselling officer who would discuss with you and decide what you want to study. And then there were forms from all institutions in Nigeria. After he had spoken with you, you could then pick a form and then he would speak to you some more... and then you went to fill it and bring it back. Everything was done for you. Once you fill the form, the counselling officer goes to look for the school. He brings the admission letter for you. 1976/77: I got my form and I'm not too sure I knew what I wanted to do. I got to my class. By that time, almost everybody was seated, and the class rep said, "Excuse me, excuse me. Jerry is here. He is the one that will represent us in art." So my class decided I was going to go and study art. That's how I went to Zaria in summer of 1977, sat for the exams, and I graduated there. Because of the crisis of economy – that seems to be a cycle – we were asked to be retained because the expatriate teachers, who really were the faculty, had to leave abruptly because the Naira had dropped in 1992/93 (the crisis at that time) and so anybody that had a first class or second class was asked to be retained. That was a directive from the Federal Ministry of Education. I had received my National Youth Service letter to go to Imo State – and we had heard stories about Imo, so I was not going to go to Imo, so I ran away. I got the letter, I took off to Imo. While I was in Imo doing the national service, the university followed me with a letter of appointment. So I finished my national service. I was 22 at that time, I came back, I didn't know what to do. I actually was thinking of reading something else, because after graduation it was "Okay, I have a degree in painting. So what?" I didn't know what to do with it. I came back and I think the head of department asked Professor Suleiman... I think he saw the naivety, the blankness in me, and he said, "Young man, you're here. You need to go and get a form to do your Master's. You are a graduate assistant, so you are not a lecturer yet." So I took off, got the form, and I was going to complain that I didn't know how I was going to pay the school fee. They said, "No, the university pays." So that's how I began to study and, at the same time, teach and, at the same time, paint, draw, design and read. So, in a nutshell, that is how I became, or I have become, something that you could call an artist.

AO: So this series focuses on the phenomenon of Japa, where, due to the political and socio-economic condition of Nigeria, a significant percentage of people migrate. What made you resist leaving Nigeria? Because I know you said your son was talking about leaving, but you decided to stay.

JB: That's a very, very good question. I don't know whether I can answer it. I'm like a sailing boat – I follow the tide. Because you see, at age 22, [I was] a guy from a hamlet that had no school, a guy that is surrounded by rivers and streams and went to school barefooted. I remember my son asking me when he saw a black and white photograph, he said, "Where are your shoes?" I said, "If you look very well, you will see my shoe." He said, "No, you're barefooted." I said, "No, look very well." He said, "I don't see any shoe." I said, "Well, don't you see a line of white from my feet to this (points to ankle)?" He said, "Yes-" "-That's my shoe – the dust." So then you were asked to be retained – it wasn't your choice – and you ran away, and then you had a letter of appointment, you came back, and then you're just trying to settle down. Your head of department tells you in the Board of Studies that you're supposed to go and pick up a form and start a Master's programme. I didn't have a choice. I think I'm one of those very few blessed Nigerians who just found themselves doing things, maybe blindly, and yet you were told you're doing well. I began to travel. I began to receive invitation to travel around the world. I usually tell people I've never paid – except for this trip – a Naira to travel. All my tickets were bought by government – German government, Japanese government, British government. […] The last show I came to was paid for. Most of my trips in other countries were paid for by government. It was this "Jerry, come and join this group to do some things for African universities." There was a particular one in which we needed to transit – the US government wanted to deliberately help African universities to transit from conventional learning to e-learning when ICT came. I'd been writing papers on multimedia. If you asked me when I was writing those papers – I don't really know what I was writing – but I believe that there was a need for teaching, learning and research to transit from the conventional way of learning to use e-materials, to do e-books, to write e-lectures and to generate intranet systems for learning. I just knew I was reading a lot, and I was communicating with a lot of guys across the globe, in the universities, and I was passionate about imparting knowledge to young people, and that was what kept me.

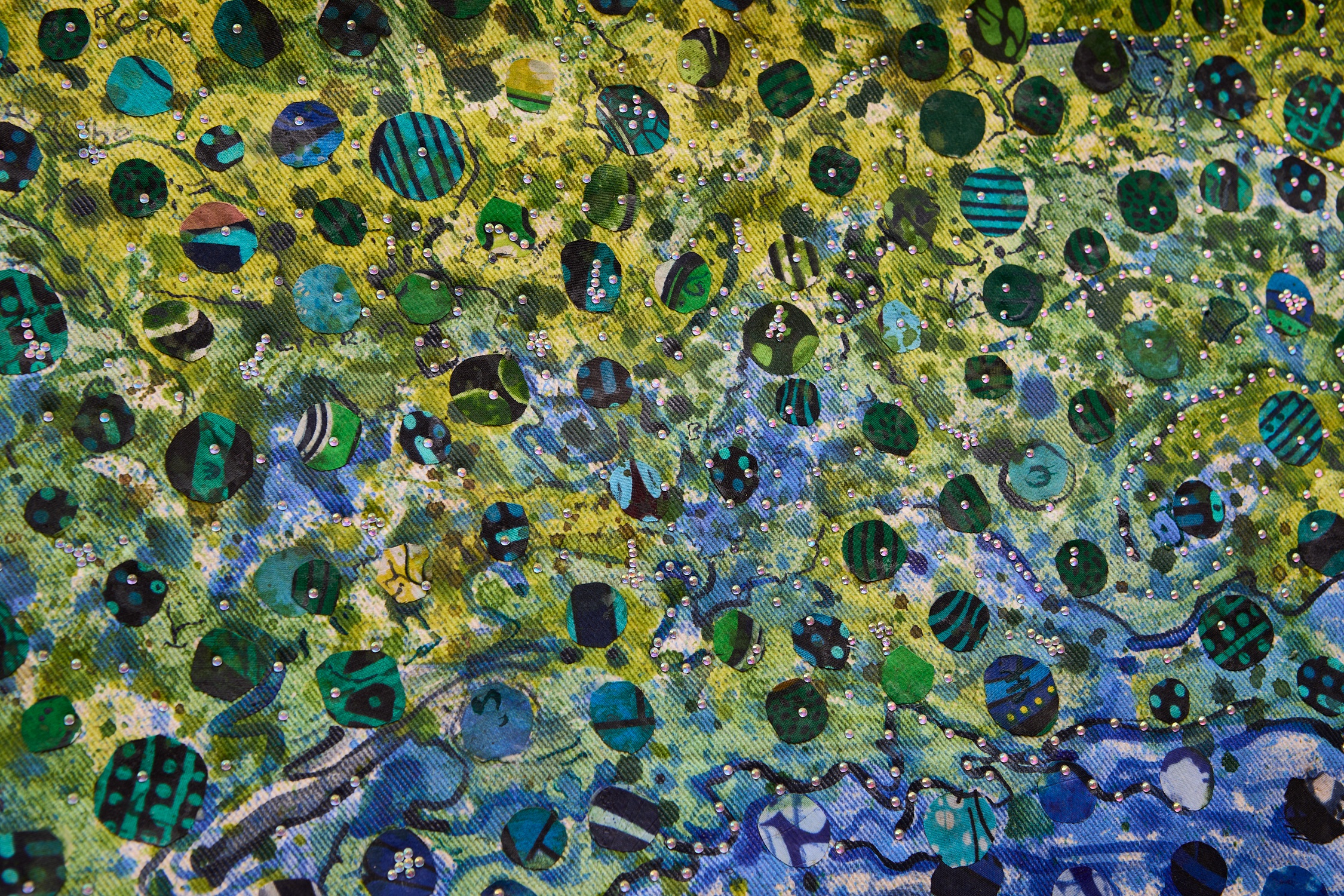

So now, why didn't I Japa? There was no need to, truly. I was having both worlds: I mean, I could go out of the country. I do know that when I arrived Lagos, my friends would say, "Why are you rushing back? Did they drive you?" Honestly, it didn't occur to me. I enjoy going out, and I create incredible body of work when I travel. I travel out of this country, but I don't miss coming back, and I don't miss going. So the challenge for me came when my last born, 29-year-old son Joshua, told me [at the] dining table, he said, "I'm done." So I thought he had had enough of me as a father. I was scared. He's a man of very few words. I said, "Done?" He said, "Look, I'm tired of Nigeria. I want to go." I said, "Just like that? Go where?" "I don't know, but I'm done." Now, that was what led to my deliberate interest in migration. I began to read and I began to interview migrants that were turned back to Nigeria – there are quite a number of them. I began to also listen to their stories. But it was when my son said he wanted to leave that it became different. There's a proverb in Africa: "When you see a corpse on the street, it means nothing unless that corpse is related to you." So the little miniatures in that room (Gallery 2) began my journey to what you now see around here. There is an immersion – these works are very personal. They are very deep. They are very traumatic, in a sense. [...] It's me writing a journal. They are writings, and they are also very fearful experiences that I try to capture, and yet visually, you could say that the colours are beautiful. There's also beauty in death. When you see a corpse – very peaceful, quiet, whether in the coffin or on the floor. That kind of visual dialogue is what these works seek to do. There are lots of figures – human beings, faces, expressions – in these. Each of these works has a minimum of 300 faces and human beings. Now, if you add the motifs, the symbols, you can begin to see the complexity of my engagement. At the end of the day, really, Jápa for me is an invitation for all humanity to engage in the whole idea of migration. Migration is actually a movement. Every human being – in fact, every organism – is in constant migration. I mean, for you to get to this place, you had to migrate, as it were, from your house, from your office, from your club to this place. You had to select what you wear, you had to make sure you had your Oyster card, or your vehicle is fuelled. Now, these works are all an attempt to show the movement of living organisms. So there's a sense in which, yes, you could say the works are also organic. They're very organic biological organisms. It's as if you're looking in a microscope. I could go on and on and on, but this is me having a dialogue with my son.

AO: Thanks for that deep answer. I noticed this pattern in the various works: you'd get things representing Sub-Saharan Africa, and then a Mediterranean body of water, followed by Europe, which is always represented as green. And I was just wondering if that recurrence was to do with people – those that were unsuccessful – making repeated attempts to get to Europe, or is it representing one particular sort of journey?

(The lure of what lies across the blue line, 2025)

JB: No, so, like I said, immigration is very complex. We all know it's a topical issue. I'm not an expert in that subject, but I am a participant, observer and a victim, if you like, of migration. The fact that in the next two or three years, my children may not be with me – they are not many. I remember my father saying, “God said you should multiply. You duplicated.” So one is quite conscious of that. I was privileged to be taught by lecturers from all over the world, my teacher that made an incredible impact in my life is by the name of Barbara House. She's British. She was the head of painting, and she taught us painting, and she was very particular about the structure of a painting, and that a painting ought to have definitive structure. So in these works, you could see a certain consistency of brown, blue and green. Actually, that's how you should read these works. The brown represents North Africa, and the blue represents the Mediterranean Sea – the sea of meditation, the sea of hope and the sea of death. You know how many people have died in the Mediterranean Sea? You know how many people have found hope across the Mediterranean Sea? And you know how some people were completely disillusioned on the Mediterranean Sea and had to turn back, or had to be forced to turn back? That's why, on some of these lower portions of the paintings, you will see feet facing the foreground.

(Attraction of the blue line, 2025: detail)

JB: The feet facing the sea represent those who are resolute, who are determined to cross the sea. It's a deliberate composition. The consistency is supposed to emphasise the issue. The circular format is also to deal with the issue of the global nature of the discourse, and the fact that it looks beautiful is also supposed to suggest deception. There's a sense in which the modern man, with all due respect, could be very pedestrian in the manner in which we deal with things, with a lot of assumptions and presumptions. And it is when you are directly affected with an issue that perhaps you find yourself humbled to be more circumspect. So again, you would notice that the last two works (We are all Jápa, 2025 and Jápa as Explorers, 2025) have introduced some reddish patterns. Those are life boats.

(Jápa as explorers, 2025: detail)

JB: Those are supposed to represent life boats in the Mediterranean Sea. And the glittering stones are supposed to represent beckoning – the kind of invitation you see when you are flying into a city in the night on a plane, and you begin to see the city. It's very deceptive. You think everything is fine until you land.

(Jápa as explorers, 2025: detail)

JB: Like the experience I had in New York when the immigration officer looked at me and said, "Where are you going?" "I'm going to Vermont." "Vermont?" "Yeah, you know it's a 25-minute drive and you are in Canada?" I said, "I don't know." He said, "Well, I'm warning you, if you cross, I will nab you." That kind of experience. So immediately when I arrived Vermont, the first thing I did was use my index finger to create drawings, and I used the soil. I stepped out of the coach that took me to Johnson village, where I went on a residency programme, and I dipped my finger on the mud, and I held it until I got to my studio, and I began to create work from that. So the index finger for me represents identity... it represents passage... it represents the complexity that all people that move have to deal with, sometimes unconsciously, sometimes painfully, sometimes gleefully.

AO: Brilliant. Thanks. I can see what you're saying about people making assumptions, and that's why the greenery represents this idea that the grass is always greener when you get somewhere. I can definitely see that in the works. You've answered the question I was going to ask about why you feel it's crucial to insert your fingerprints into the work as well. Speaking of the stones that are in the larger pieces, what's the process for making sure that they actually stayed on the fabric?

JB: That's very interesting. One of the challenges a teacher of art confronts is that you have to help the students produce work that lasts. And so, whether you like it or not, you have to let the student know that the materials you use must be of quality and of enduring. But I'm not just an art teacher, I also create work, and I draw energy from my students. People say, "Why don't you go and be a full-time teacher?" I can't. My wife knows – she's here – if I am sick, I will take [myself] and put [myself] in front of a class: I'll be well. That's the kind of energy that I draw from my students. There's a course we teach at the undergraduate level. We call it Studio Practice. And the whole idea is to help students know their materials and make sure they use them in such a way that, if they produce work, the work lasts. But you know the discourse at the moment – the ephemerality of art and the way in which conceptual art has brought a new discourse in the relevance or not of whether a work should last. Some artists will tell you it's not their business when they create a work of art, whether it lasts or not; it's the business of whoever loves it and buys it. Again, when you teach art, you have to balance that discourse. You know that somebody paid for the guy to go to school, and somebody wants the guy to be able to put food on the table for herself or for himself. You also have this sense of responsibility that, okay, you want to buy my work.

Just before this talk began, I was telling one of us here that in Africa – and I think I can speak for many African art schools – the challenge of students, many of them very poor, is how to buy ordinary cartridge paper, which is the most standard paper for drawing. Students can't afford cartridge paper. It's not even available to buy. How much more for canvas? So the thing is, I tell the students in the studio practice class: "[...] If you did a painting, oil on fabric, please write 'oil on fabric'. Don't say 'oil on canvas'. They are not the same. Of course, if it's a drawing on acid paper, [...] he (the buyer) should know that this drawing was done on acid paper." Do you know that cartridge paper, handmade paper, whatever kind of paper, are better paper? Once a paper is acid, the longevity of such an artwork is compromised. But again, you know that some artists, when they become successful – even if they are not successful – they don't care about the material; their interest is to produce work that comes out of the bottom of their heart. [...] This is the newest direction that is coming out of my studio – these works. I've never done something like this. I have something similar with fabric, but not in the direction of Jápa. I deliberately took time to make sure that all the knowledge I have from Ralph Mayer – those of you who are familiar with the book [by] Ralph Mayer: Art and Material Techniques – I've applied them. I know Ed was asking, "Some collectors are saying, so what's this? How would it not fade?" I was a bit irritated, but it's a sense of responsibility, so I've dealt with that. After the works were created, I put a sheen over the work. You can't see it with the naked eye; the work can last as long as oil on canvas or acrylic on canvas. Ofcourse, if you want to destroy anything, you can – there are many attempts on the Mona Lisa.

AO: Yes, very true. Did you use glue? What exactly did you use (to stick the stones to the fabric)?

JB: I used white glue. My university has a Department of Textile Technology, so I've made use of the professors there. […] I took a work to them, and I said, "This is what I'm doing." They looked at it, did a study of it. "Okay, fine. Can I come and see what you're doing?" I invited them, they came and looked at it, and we tried to wash off the work. [...] I applied some acid, some tough, unfriendly chemicals – it was okay. So really, again, it's not my business whether you like the work or not, but it's my responsibility to make sure that, if you decide you want to own a work like this, you have the stamp of the artist and, of course, by extension, the stamp of Ed. It's good that you're asking. Now, the stones – that's the tricky one. I first thought that if I use the traditional pressing iron – many of you may not have even seen it – you use charcoal to heat the iron, and then you put pressure on it. But then there are new machines: now there are electric machines, and I send it to him and, after that, we applied the modern machine that presses further. So if you look at the back of the works, you would see a depression to show you how deep the stone had gone. So it's very permanent. Of course, if you want to destroy it, you can. Andy Goldsworthy is one of my favourite British artists. Andy Goldsworthy believes that any work that goes through whatever process has been translated into another level. That I love. He doesn't believe an artwork can be destroyed, and that is what led me to begin to collaborate with termites. I create works now based on collaboration with termites. I give my work to termites to eat, and when they have eaten quite a chunk, I take it back and finish up. If you go to my Instagram page, you will see that I have some short videos on that collaboration.

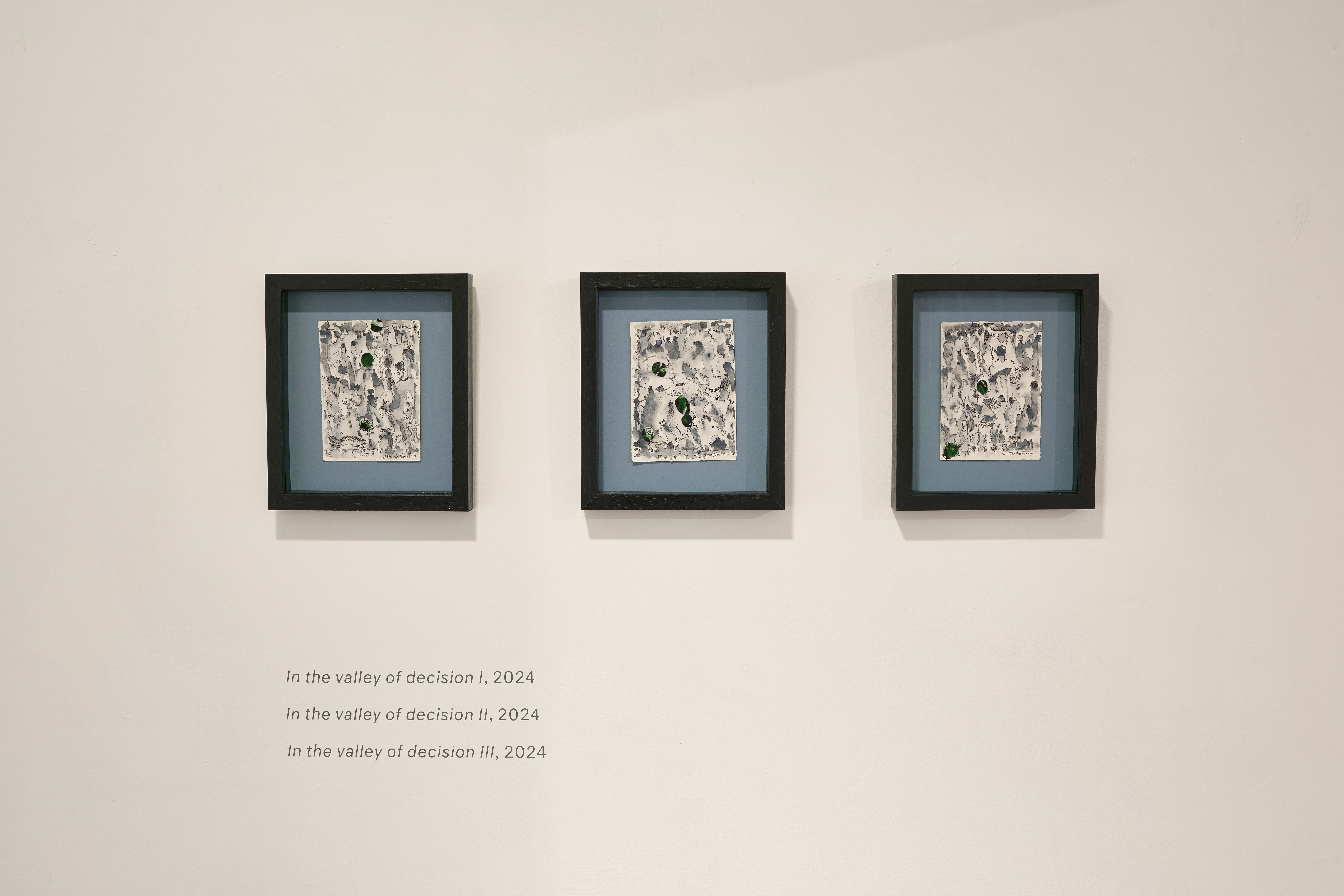

AO: Really fascinating. I need to add you and start following you on Instagram then, because I was not aware of that... So we've talked loads about the larger works, but I'm not sure you've said much about the smaller pieces.

(Installation view of Jápa exhibtion, photo by Rocio Chacon)

JB: The miniatures were the beginning of my conversation with the subject of departure – my children. How does a parent deal with a child that has made up his mind or her mind to leave you, or has grown and you know is going? This is different. This is a child telling you he wants to leave Africa. He wants to leave Nigeria. He wants to leave your house. And you know that you cannot support – you may not be able to support – him or her when he leaves. Now that, for somebody like me that has only two doves – my father says, "You duplicated" – becomes very difficult. If you had many children, with all due respect, then you could say, "One goes, there's still some more." But it's different. My children grew up with us. We are like friends, you know? We jive together. I couldn't deal with it, truly. I couldn't deal with my children leaving, but I knew it was a reality. Most of my students that I've taught are all here. Hassan, when did you graduate?

HASSAN (SPEAKER 1): 1981.

JB: 1981, I taught him. So he's been here since. There are several of them. I was going to tell Joshua (my son), “Look, you need to talk to Hassan,” because Hassan knows the ropes. He knows the corners, the parts, the pathways across the Sahara Desert. These are some of the challenges you face when your son says he wants to leave, and I have my reservations about his ability to survive outside.

HASSAN: He will never know what he can and can't do if he doesn't try.

JB: Yes. As parent and as an artist, I deal with my studio – the tiniest paper that I have is my laboratory. When I need to deal with a problem, when I need to deal with a situation, I draw, and in drawing, I'm able to find some form of equilibrium, some strength, some resolutions, the ability to construct a survival technique that is very, very psychological. It's not physical. Then I'm able to deal with those things. If you go into this room (Gallery 2) and you take your time, you're going to see a lot of children in those tiny drawings.

(Migrant's dream of green lands II, 2024)

(Migrant's dream of green lands II, 2024)

JB: Those children represent my children and perhaps your children who have left you or who you are struggling with. There are many of us who don't even know where our children are, so we deal with all these struggles, and I find solace in that. You know why? In those drawings, I'm able to create my own Nigeria, my own Earth, my world, and I can decide who is big or who is small. In that drawing, I can decide who is weak and who is strong, and that helps me to deal with the reality, or the so-called reality, that I face physically.

AO: Thanks for that poetic answer. [...] I'm curious about your future – are you working towards another exhibition? Have you got any other artistic projects that you're working on?

JB: That's a very good question, and I pass it on to Ed. Very quickly – I hope I don't bore you – I have been very suspicious of galleries, because I have never had a good experience. You can imagine, forty-something years of art practice, and boy, I have works in my house. My wife is always complaining, and maybe that's why the termites decided to start. Like I said, I draw energy from my students, so I give an assignment, and when I'm marking, I see some direction, and I rush back to my studio after class. So I have a body of work. I sent him (Ed) a collection of work in which it's all collaboration with termites. I collect pieces of wood from the bush, I bring them to my house – because my house, we share them with termites – I submit the wood to termites for two, three years, and I watch what they do on the wood, and then I take back the wood and produce work out of them. So I have a body of work like that. I work serially, because I direct students to do projects, so I must also show that one can construct problems. I have a collaboration with termites and I have another series that is called the Spillage series, which I started in 1990. The Spillage series had to do with the destruction of oil in the Niger Delta. So I have a body of work that deals with that. I have another body of work that is called Hard Times – you probably have heard of a certain military ruler called Abacha (Sani Abacha). During that time, I was a young married man struggling to establish a home, and it was not easy. So I produced a body of work, black and white, titled Hard Times. I have another that is called the Melting Planet series. In the Melting Planet series, I'm drawing inspiration from the Bible, in which it says the world is going to end with fire – it's going to be burnt with fire. And we're talking about global warming, so I'm asking the question, "Is that related, or is it a coincidence?" So I have paintings that deal with that subject, and I use motifs from ancient civilisations on a liquid picture plane, and I watch how these images dissolve. That also had taken me to the Global Village series. I have a body of work all in those directions, in my journey as an artist.

AO: Great.

JB: I also do performance. I've done some performances in the river. My university, which was established by the British government, is greener than some universities in the South. If you fly over Zaria, over the university, you will not see a single building. You will see foliage. And so, as I retire, some people begin to cut down the trees. It's painful. So what I do is I try to rescue some of these chunks of trees, I slice them into cake-like format, I paint them and create and do a performance around it.

AO: Yes, Jelili – like I said, I've been doing my research on Jelili Atiku – told me about you doing performance and helping to encourage him with performance. So now I'm looking forward to seeing your performances on Instagram and your next series of work over here. Do people have questions directly?

HASSAN: I'd like to say that Professor Jerry Buhari was everyone's favourite lecturer from the days in my teenage years when I was a student, and he would take me right around the campus doing life drawing, doing landscapes, and then we did still life, we did imaginative composition, we created a world around us, and we had the tools we were given as well through the curriculum and through his personal input about thinking about a world which we did not physically see, which we perceived intuitively. Now this work is extremely exciting for me thematically, and I find it particularly deep in the sense that that kind of thematic engagement is not very common among my peers who work in Nigeria today, where aesthetic has precedence over that sort of conceptual (work) in trying to talk about these things, these factors I was talking about, which is very key and very important. But my question really is, apart from that lecture, in reflecting on the historical and contemporary movement of Africans across the Atlantic, we often say that we will go willingly, but do we actually go willingly? There are many underlying factors, such as globalisation and capitalism driven by external economic pressures, which remain strikingly similar, both in the first migration – the first Japa – where we were forced into slave ships, and the current trend, where we are forced into boats, dinghies and anything that floats, because we are trying to get away from a situation that has been brought upon us by the Global North. So this continued migration rate is concerned about brain drain and the loss of human capital across key areas. Do these dynamics feature as a thematic concern in your work or in the broader discourse of African contemporary art? Do you have the economic aspects (in mind), where Japa is not only because somebody is bored at home and wants to see the world, but where we're actually critiquing globalisation, critiquing European incursions, exploitation of Africa – that's then bringing about debt, which is bringing about the loss of quality of life that then brings young people to migrate, inevitably causing a drain on our society in terms of development targets?

JB: So I have a very, very suspicious student of colonisation, because I think that it has become a rather — [forgive] the use of the word — masturbated word, for me. The discourse of colonisation may have to take a rather restrained approach, in the sense that when you blame colonisation on the state of your being or the state of your country, you are perhaps looking for an escape route. I'll be 66 in July, and the woman that trained my father was a missionary from Scotland. My father was led to Christ by this young girl, who was not married. She came to Nigeria, and on account of that, she taught him how to read and write. My father trained his only brother, who, after graduation, trained all his children, including myself. So when you talk about colonisation, it may not go down very well with me all the way to the terminus, right? Because I am a beneficiary of colonisation. If this woman did not come to Africa and train my father — who was a drunk, had already lost almost all his teeth, and spent time in that hamlet — it’s not a village, [there’s] nothing there! [He] slept through mosquitoes and all of that, and he now trained his brother, went to the farm, farmed ginger, trained the brother. The brother graduated, went to a missionary Teacher Training School in Toro, Bauchi State, and came back and took me. I was the age of four when my father took me. My mother was screaming and raining abuses on him. This is a personal experience. Don’t get me wrong, the evil of colonisation will live with us, but the evil of Africans who have collaborated with colonisation and colonialism will also live with us, and somehow we need to begin to share the blame and the benefits. So as a scholar, I have been very careful in this narrative.

Having said that, you raise very complex issues about migration — why do people move, and what are the reasons for moving? It’s very complex. It’s not an exhaustible subject. What I’ve done in these works — if you take your time to look at that, I wish you do — get a piece of paper, cut a square or rectangle, and place one on just this (section of the work), and you will see an incredible story — just this portion. Move the paper […] and you will see a lot of stories. If you go to the larger works, which are the last works that I produce, you will begin to see the iconic architectural edifices of the countries of Europe: the Eiffel Tower, the Acropolis. These are drawings, very intricate, tiny drawings, and they are meant to challenge your visual perception. They are meant to tickle your thinking, to expand your understanding of what Jápa is, and to actually render it complex. Joshua (my son) wants to leave because he doesn’t think he has a future in Nigeria. But his elder brother thinks, “Look, people are doing it well and surviving in Nigeria — I will take it on.” Two brothers, same parents. The discourse is very complex in any case. A lot of British people are in Nigeria now — they have Japad to Nigeria — as gory as the story is told in the Western newspapers. And the same Nigerians are also leaving. Somebody was asking me, “Jerry, I suppose you’re better off here now, after all, you’re looking well in this town.” I told Ed that I have spent time in these villages around Aldershot. My wife and I came back from Aldershot yesterday. We have friends there who invited us, and they know I love the village, so we’ve gone round most of the villages around Aldershot that some of you who live here may have never heard of, like Shere. Shere is one of the most beautiful villages in England. You know what they are known for? Gardens. Every little house has an incredible garden. No matter how small the garden is, it is so exquisitely made and kept. I’ve taken time to draw, and I’ve said maybe, if I get a grant, I’ll come and spend like two weeks and create works of the country — landscapes of this country — and who knows, it may decide to get more guys from those villages to come and live in Nigeria, or they may encourage me to come back from time to time.

The discourse is complex, but one thing I want as a takeaway from these honoured guests is that I want you to see migration as an existential phenomenon that engages every human being — every organism, even micro-organisms. There’s a sense in which we need a more holistic approach to the way we deal with migration — a more humble approach to it — more over and above the way some of our modern political leaders are handling the issue. At the end of the day, we are all humans, and we are constantly looking for a better place. And when we move to a better place, we often add value to that place [more so] than we take out value from that place. Even when you encounter — in Japan, when you Japa to Japan, where it is said to be a very innocent and very harm-free zone — if you meet somebody who is very rough, it teaches you to be very cautious, isn’t it? Not to take anything for granted. So I think Japa-ing is something that all of us should be interested in and should engage in. In fact, I raised an issue in the title of that work, and I titled it Jápa as explorers (2025). It’s a way of interrogating this whole idea of colonisation. Because when the West went to Africa, they were considered explorers. But why are the people leaving Africa to Europe not considered explorers? The bigger work is titled We are all Jápa (2025), and the whole idea is to invite us to a more inclusive discourse about this whole business of Japa. It’s a very complex subject, and it defines the very nature of globalisation in which we find ourselves. I’m not a politician. I’m just an ordinary artist that engages in a two-dimensional surface but I think that there’s a sense in which the empathy that I bring to bear in the way in which I see the world is supposed to be seen as adding value to the discussion.

SPEAKER 1: In response to your nuanced response on colonialism, and given that your more [...] holistic approach to migration, as a decolonial idea, what are your thoughts around not having any boundaries [...] - to take away the borders and have a different system in which people migrate, rather than having to come through borders and having to prove themselves, or having to financially be a certain type of person?

JB: I feel that's an extremely thought-provoking question, because to imagine a world without borders is dangerous. It's very dangerous, right? I mean, in your bedroom, when you are undressing, you cannot afford to have your in-law come in. Yes, it's as simple as that [...] there's a need for order. Any society that does not have laws and order is finished. [...] So let's start from that basic understanding, because when you talk about borders, there are geographical borders, there are psychological borders, there are economic borders, there are emotional borders, gender borders. So the world is made up of borders. What I think we need to add in that discourse is empathy, is humility, is understanding that the human species – I like to use the word Homo Sapiens – the Homo Sapiens is supposed to be more humble. I don't see that in the modern world, with all due respect. We ought to be our brother's keeper or our sister's keeper. We ought to be able to accommodate people with their differences. Once you understand borders within the context – I'm trying to construct a framework for dealing with migration and the issue of borders. I hope I'm not misunderstanding you. I hope I'm not oversimplifying it. But I do think that in my humble submission and my little study of migration and the way in which I deal with my son, because I'd like to be very practical – I'd like to deal with the practical experience. If my son, for example, wants to come and study in the UK, and I've done some studies, and I know he cannot. I'm sorry. I know he cannot, but somebody told me, "No, you have not tried him, you are being judgemental." So I said, "Okay, fine. I will give the background. I will give him the support, but I'm not going to be around all the time."

SPEAKER 2: So when you say that he can't do it, are you saying financially, or are you saying the work ethic and all of what he has to go through?

JB: So this is how a parent thinks. I don't know whether you are one, with all due respect. A parent has a problem of protection. You have this desire to be protective, even when the guy is grown up, and when he went to school, he didn't even call you. He fell sick and got better. He didn't tell you. It's different. This physical disconnection... If he's in Nigeria and there's a problem in Lagos, I can enter the night bus and go and look for [him]. Maybe you wouldn't do it here in Europe, but back in Africa, if my son is 35, he's married, he has a problem, I will go. I know that here the guy will ask you, "Who asked you to come?" – I understand that, and I respect it. Truly. I respect it. [...] My son – the older one, he's 34 – had come around Abuja for a wedding. He knows the mother will faint if, if she hears that he came by road, because my children have never travelled by road from the South to the North, since the issues of bad roads and insecurity. But he knew the mother would not know. So he travelled and told the younger brother, "Don't tell mum." It was when he arrived that the younger brother called to say, "Caleb is in town." So the mum said, "How did you come?" You see, he came by road. "What?!" He made it. Nothing happened. He actually enjoyed the trip. I don't know whether I got [your question]. If I haven't, I'm sorry, but that is the way I respond to your question. Any more questions?

SPEAKER 2: So for me, I think the discussion is really good, and to hear more about your thoughts and how you generate your ideas, and I love the theme of the work that you're actually doing. I definitely wouldn't agree with your comment around being a beneficiary, but that's another discussion altogether. But I want to know: what would you say to your, your 30-year-old self? If you were able to go back in time, what would you say to your 30-year-old self in terms of your work?

JB: Why should I take that journey backwards? [...] I have had fun. I've done an incredible body of work. A lot of it is not liked, it's not known, but boy, I'm having a terrific time enjoying to create work. I do know that 50 years, 100 years down the road, my works may be seen differently. There is a very, with all due respect again, limited interest in reading. If you are interested in artistry, you would know that there was a lot of reading in artistry. My artistry lecturer was British, David Heathcote, and the way he taught us how to study artistry, I've never seen it anywhere, even the schools I visit in the US. He gives you an artwork. He asks you to draw it, then he asks you to write a short story on the work based on what you read, and then he asks you to set it aside and imagine you never read about it, and critique that work. That kind of pedagogy I've not seen. Do I do it? I hardly do it. Why? The students are not interested.

SPEAKER 2: My question wasn't a criticism of your work, it was actually to say, what was your mindset? Is your mindset now different from the 30-year-old person when you started the body of work that you've done? But take that aside. The other thing I wanted to say to you is, what piece of artwork did you do that made you decide, "That's it. I'm not going to ever do anything else. This is what I want to do for a living"?

JB: That's a simpler question. So in 1989 I was looking for an opportunity to do a solo exhibition. I began to apply. At that time, the places that exhibited in Nigeria were foreign cultural centres like British Council, Goethe-Institut, Russian Cultural Centre, Alliance Française – those are the kind of guys that really sponsor art exhibitions in Nigeria. And it was only either in Kaduna where you had the British Council – they had offices in almost every state, not now – (or the Italian Cultural Institute). So I began to apply, and I got the Italian Cultural Institute - the director, Dr Gabriel Tombini. I sent him a portfolio of my work, and he called me. It was landline then, there was no cell phone. He said, "I like your works, but I don't believe they are your works." He was very frank. "So I'm coming to Zaria to look at what you have, and then after we have spoken, I will determine whether I should show you, because you are coming to Lagos for the first time. I don't give artists who have never exhibited first-time solo shows." So lo and behold, he came, took me out to lunch in a local restaurant we had, and then I brought him to my house. I used my boys' quarters as a studio, and they looked at the works, and they said, "Jerry, I think I can give you a show, but you are not ready." That was 1987 – the time I was trying to convince my wife that I was a good guy for her to marry. So he said to me, "If you want an exhibition from me, it has to be 1989." So I had to wait for two years. With all due respect, Alliance Française could give you a space, but I didn't care. Same thing with British Council. But Gabriel said, "No, you have good works, but you need to have like 65 works, then select your best and exhibit." And that's what happened. So he gave me November 18, 1989, and I had my first solo show in Lagos. And that night, 80% of the works were sold, and I got the money, and I got married to this lady. So that [settled it for] me. Prior to that, I was actually giving up. I was going to come to the UK or somewhere to read law or to read something like that. I wanted to read something that I thought was more challenging. Art for me comes effortlessly, and the successful exhibition kind of confirmed that I may not be on the wrong path. Since then, I've never looked back and the joy for me is I get to meet great guys like you.